With no knowledge of genealogical research methods, we headed to Hancock County, Georgia, with no idea what we would find. About halfway between Atlanta and Augusta, the GPS told us to turn off I-20 and travel south for about 30 miles. As we left the interstate, we ventured farther from the beaten path into land that must have looked much as it did 200 years ago. It was heavily wooded; there were few people and few signs of habitation.

The time machine was working, though, as several signs told us that this was an historic church, founded in 1786, and the home to creation of the Georgia Baptist Convention.

After a short stop to check for a cemetery and finding none, we proceeded on about two-and-a-half miles to the county seat in Sparta. As we approached town, it was apparent that this area had once been prosperous, but the glory days of Hancock County had passed more than 150 years ago.

On the inside, steps lead up to a massive court room, straight out of To Kill a Mockingbird. Obviously built for a time before electric lighting, tall windows flood the courtroom with light.

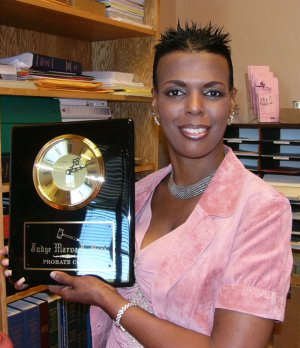

Back on the first floor, signs directed us to the Probate office. Inside, we were greeted by Judge Marva L. Rice who looked more like a super-model than a probate judge. Interrupting her lunch, we told her about George and how little we knew about him. She first showed us the graves registry but there were no graves in the county recorded before 1800.

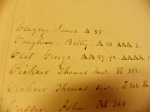

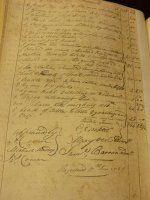

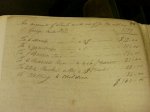

We located the first record and found that he was dead. Of course, we knew he was dead in 1799, but he did not create a single record in Hancock County before he died. The first record on file was cryptic entry dated March 21, 1799, in which Mary Vest and Samuel Barron for the estate of George Vest are posting a $15,000 bond. Now, $15,000 is a lot of money today, but in 1799, this was a fortune. Unfortunately, no further documents explained the bond.

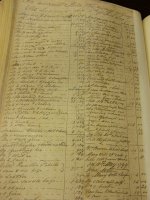

The next record was an inventory of the worldly possessions of George Vest. The first thing that jumped out at me was right there between "25 head of hogs" and "4 bells & collars"--George Vest owned a "Negroe woman" valued at $450. I looked up at the judge enjoying her lunch as I realized that my ancestor could have owned her ancestor. How could they have thought that that was right?

The rest of the items show the possessions of a fairly prosperous frontiersman. He had plenty of tools and the latest and greatest gadgets of the day. In a land where possession were limited, he had many. He also owned four books: a hymnal, The Bible, and two school books.

But how did George earn his living? There are a few clues to this question. Most men at that time listed their occupation as "Farmer" and there is little doubt that George's family grew or raised most of what they ate. George also apparently had some income from retail sales too, as indicated by a long list of accounts receivable at the time of his death. What did he sell? Most likely bacon, hams and tobacco--with 25 hogs and 1,100 pounds of tobacco, he obviously had more than his family would use.

The laws of 1799 were not kind to women and Mary had to stand watching as all of her household goods went on the auction block just a few weeks after her husband's death. She spent more than $200 to buy some of her own dishes and household property. How did she feel having to pay more than $30 to buy her own bed?

There is an item in the expenses that says, "Paid her dower - $59." This has been previously transcribed as "dowry," but dowers were a part of the social structure at the end of the 18th century. When a man died without a will, his wife had roughly the status of a worker when a company went out of business. The dower was sort of a severance package for the widow. It is no wonder that Mary soon remarried.

Mary had one more heartache to absorb in the months after George's death. By June, her co-administrator of George's estate, Samuel Barron would be dead.

We went looking for my ggggg-grandfather and found my ggggg-grandmother was one strong lady.

|

When we entered Hancock county, the first sign of civilization was a white frame Baptist church that looked like any other of the hundreds that dot the rural south. The church was simply designed with an elegant gabled roof-line topped by a tin steeple.

When we entered Hancock county, the first sign of civilization was a white frame Baptist church that looked like any other of the hundreds that dot the rural south. The church was simply designed with an elegant gabled roof-line topped by a tin steeple.

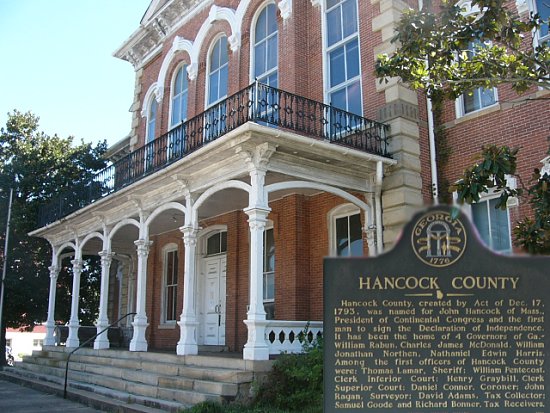

One of the few open buildings in "downtown" Sparta was the Hancock County Courthouse. The red brick building sported an unusual portico topped with wrought iron.

One of the few open buildings in "downtown" Sparta was the Hancock County Courthouse. The red brick building sported an unusual portico topped with wrought iron.